Book: Tears of a Komsomol Girl

Author: Audrey Szasz

Type of Book: A hybrid of true crime, photography, literary fiction, historical fiction

Why Do I Consider This Book Odd: Jesus Christ, this book…

Availability: First published in 2020 by Infinity Land Press, you can get a copy here. My copy is from a 2022 reprint.

Availability: First published in 2020 by Infinity Land Press, you can get a copy here. My copy is from a 2022 reprint.

Comments: I said in yesterday’s look at Grady Hendrix’s take on the final girl trope that today I would be discussing an anti-final girl, and while that is sort of a flippant way to broadcast a new entry, it’s still an accurate assessment. Arina, or Arisha as her mother calls her, dies several deaths in this novel, and though she (sometimes only) dies in her dreams, her deaths are no less real and devastating for that fact.

This is one of those times when I realize I’ve come across something rare and so odd I am almost uncomfortable trying to discuss it. I know there are subtexts I will miss. I know that there are ideas and emotions Szasz is trying to convey that I will overlook entirely. But the inevitability that I will get things wrong also comes with a bit of excitement, especially if it means others who have tackled this book come and discuss it with me (hint, hint).

Arina is fourteen and lives in Russia during the heady days of glasnost and perestroika, an uneasy time when the culture change from communist control to a more open approach to trade and politics is just beginning. The specters of the old ways are crashing headfirst into the dangers of the new ways and Arina is trying to find her way in the midst of this change. Alongside Arina’s arrogant yet hopeful explorations, the Ripper of Rostov, one Andrei Chikatilo, is murdering people in horrific, gory ways and he too is a specter that haunts Arina.

This is a novel with an unreliable narrator and pays no attention to a linear progression of time. Arina, an accomplished violinist who aspires to become a professional musician, attends a boarding school for gifted students but she also attends a school near her home, sometimes returning to a dormitory, sometimes returning home to her mother. Sometimes she is an orphan, sometimes she lives with both parents, and sometimes only her mother is at home.

Arina’s versions of her life are always grounded in some very specific realities, mainly that she is small and looks younger than she actually is and she knows she is prey even as she hopes one day to become a predator in her own right. She does not want to be a murderous predator, but rather hopes her already jaded approach to male-female interactions enable her to make “connections” that will serve her well when she is an adult. She approaches the dying days of the USSR by graduating from Young Pioneers to becoming a Komsomol girl, and she approaches party politics the way she does her sexual interactions – it is something she does with an eye to building connections that can later assist her in her future ambitions.

Arina doesn’t hesitate to discuss herself as a bratty girl. She complains endlessly about the cheap, man-made leather shoes her mother purchased for her, one of the consistent threads in her different stories, she admits she has the sense that she is better than others, and she engages in uneasy behaviors, like covert masturbation as her family is gathered, watching a video of one of her performances. She does not worry that her recitations of her less positive qualities will ever hamper her, as she is profoundly confident in her capabilities to navigate the world around her and manipulate the situations in which she finds herself. Or at least she thinks she can until she encounters the killer she calls Satan, Mr. Chikatilo, and it is in his presence, even if it is only in her nightmares, that she encounters a force that genuinely reveals her vulnerabilities and forces her to regard herself as a victim who does not have control, dignity or even bodily integrity if a strong adult decides to take them from her.

It’s so tempting to discuss this novel in terms of the collision between old communism and the changes that awaited Eastern Europe after the dissolution of the USSR and the fall of the Berlin wall. Chikatilo, born in Ukraine right after the Holodomor and right before the horrors of the Second World War, endured a savage upbringing. He may or may not have lost a sibling to cannibalism, but undeniably he lived in dire poverty until he was an adult. Shaped by chaotic political violence, it would have been difficult for him to conform to the necessary self-control required in the USSR even had he been sane. But he wasn’t sane and the structure that communism would have given him he ultimately devoured with every person he killed. Arina, on the other hand, raised in structure so confining that she lives a life longing for ultimate freedom, was more than poised to leap into the brave, new, unstable world of travel, work and freedom but was herself devoured by the chaotic past, and it happened over and over, each dream of her death at the hands of Satan worse than the one before.

But that is just one of many ways to look at this astonishing novel. Another is that all the versions of herself that Arina conveys are elements of the experiences clever but underprivileged girls faced in the USSR, even as it became Russia. One could see her different stories as the results of small changes in her environment that, when reset, left her on a similar but somewhat different path. She is in turns a girl from an abusive home where fathers beat unfaithful wives, a girl sent to an orphanage when her parents died, a girl who was preyed upon by those in power in a supposedly classless society, a girl who would be ravaged by the past before she could begin living her future. But Arina also represents every teen girl anywhere. The anger she felt over her man-made leather shoes that looked cheap and did not hold up to the weather well, being unable to please her mother no matter how much she practiced her violin, being in possession of a new body and the new power that comes with it – this is the state of all girls everywhere. The arrogance of youth is universal, as is its hope. I would have been an age peer of Arina’s and her inner life was not wholly different from mine and the main difference is that Arina, by virtue of where she lived, was more or less born to be prey and no matter how her life changed from chapter to chapter, her end would always be the same. She may live a different life during the day but at night Satan always takes her in her dreams until one day she does not get a chance to rewrite the story of her life.

Arina’s dreams and reality can be summed up in a passage where she meets a man with whom she begins a sexual affair (and keep in mind she is fourteen and looks even younger while he is very much an adult), a man she calls Uncle Vanya. She walks past his chauffeured car and it is so obviously a symbol of the wealth and power she one day hopes for herself that she stops and looks at the car intently, seeing her own reflection shining back at her from the immaculately clean vehicle. This seems like a great symbol – she sees herself in the objects that represent a life far better than the one she currently lives. But then the chauffeur steps out and threatens her, telling her to leave. Uncle Vanya tells his driver to stand down and takes his measure of Arina, feeling her out to see how much intolerable behavior she will accept. When she lies and says she is much older than she is, he understands she is both too young to understand the near-Faustian bargain she will make if she accepts the ride he offers, but is old enough to feel as if she controls the situation since she caught the eye of a much older, wealthy and powerful man. And in the end, Arina does not seem to mind what Uncle Vanya and his friends want from her and because she is willing, she does not see it as a violation because she experiences true violation every time she dreams of Satan. It’s also interesting to note that one of her sexual fantasies where she is not raped and murdered involves a very involved dream about a Lenin statue coming to life.

Arina’s dreams and reality can be summed up in a passage where she meets a man with whom she begins a sexual affair (and keep in mind she is fourteen and looks even younger while he is very much an adult), a man she calls Uncle Vanya. She walks past his chauffeured car and it is so obviously a symbol of the wealth and power she one day hopes for herself that she stops and looks at the car intently, seeing her own reflection shining back at her from the immaculately clean vehicle. This seems like a great symbol – she sees herself in the objects that represent a life far better than the one she currently lives. But then the chauffeur steps out and threatens her, telling her to leave. Uncle Vanya tells his driver to stand down and takes his measure of Arina, feeling her out to see how much intolerable behavior she will accept. When she lies and says she is much older than she is, he understands she is both too young to understand the near-Faustian bargain she will make if she accepts the ride he offers, but is old enough to feel as if she controls the situation since she caught the eye of a much older, wealthy and powerful man. And in the end, Arina does not seem to mind what Uncle Vanya and his friends want from her and because she is willing, she does not see it as a violation because she experiences true violation every time she dreams of Satan. It’s also interesting to note that one of her sexual fantasies where she is not raped and murdered involves a very involved dream about a Lenin statue coming to life.

This is a brutal novel but even in the most excruciating passages discussing the harm that comes to Arina, Szasz writes the horror with an almost poetic hand, but other times her hand holds a hammer, as does Satan during one of his attacks on Arina.

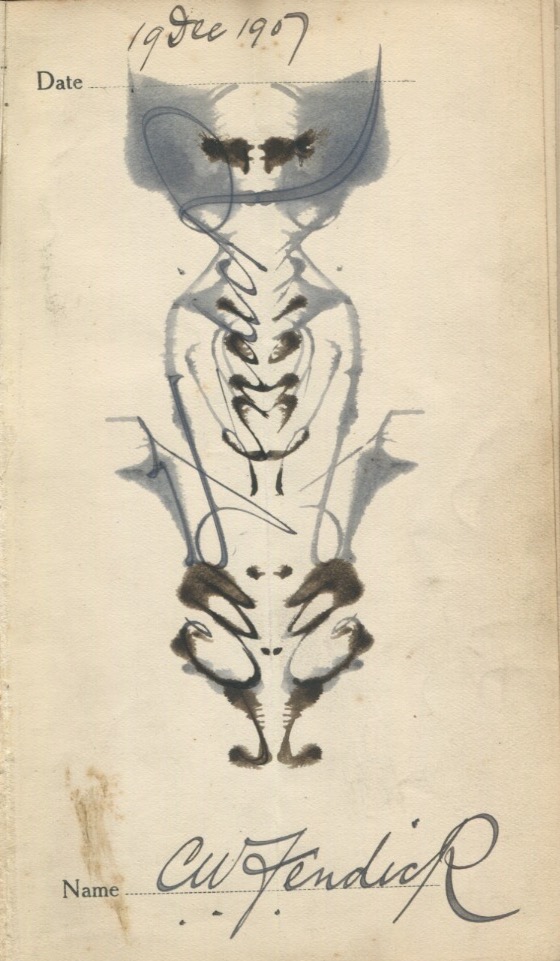

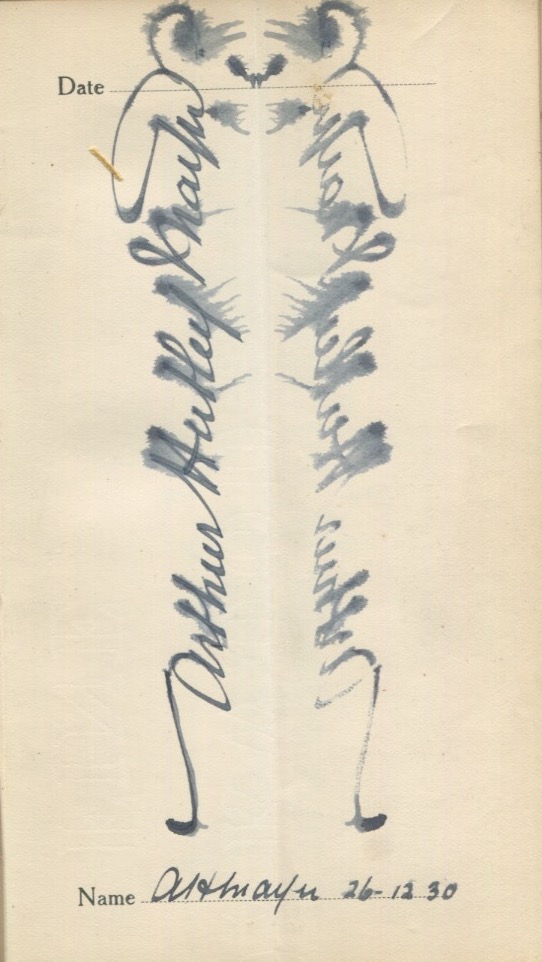

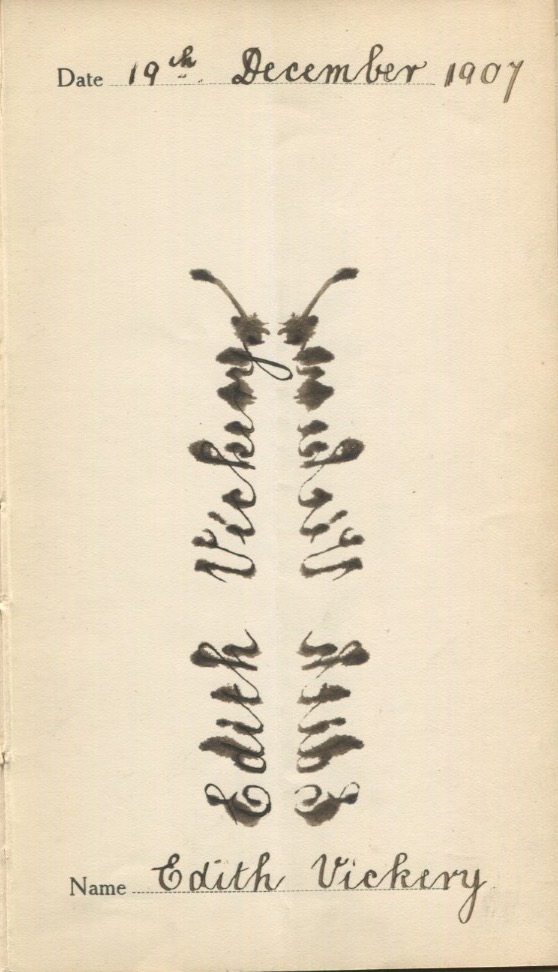

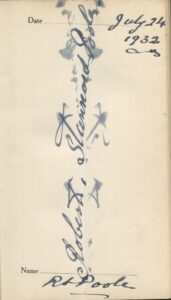

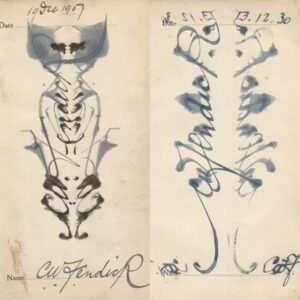

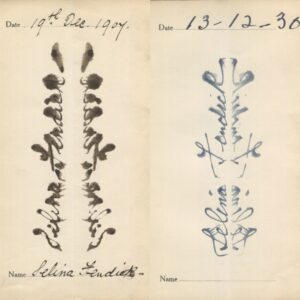

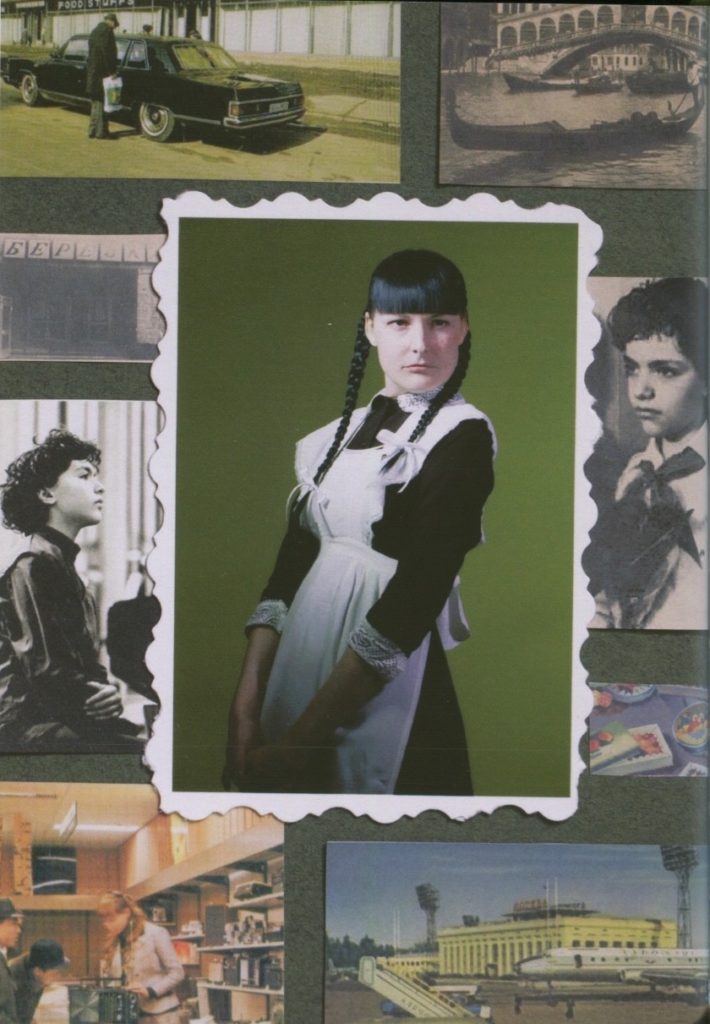

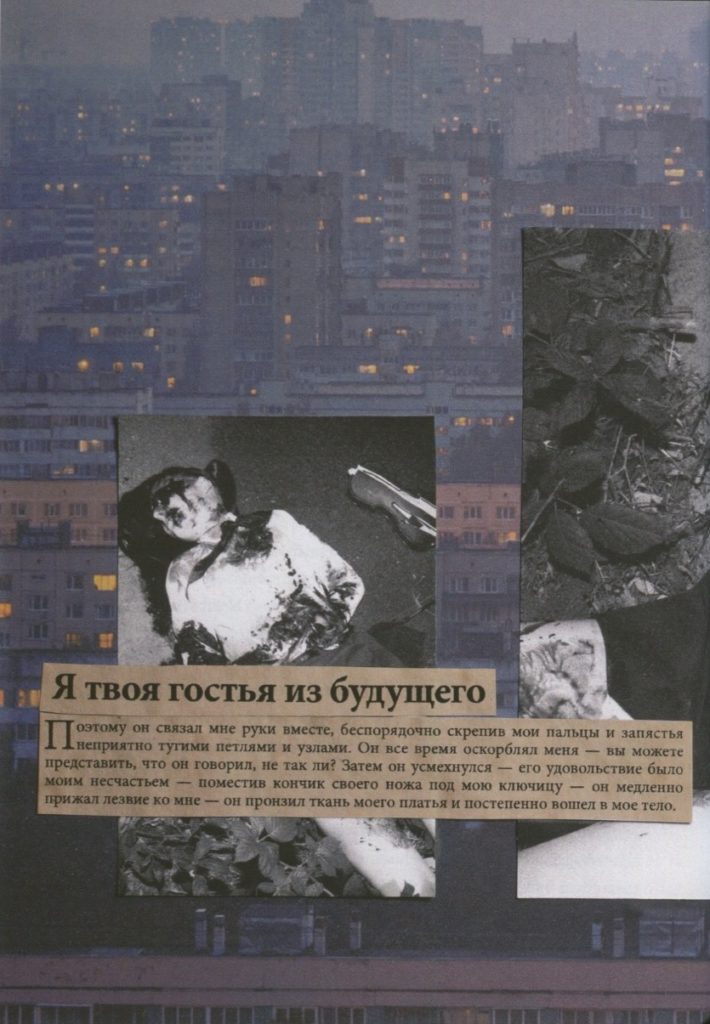

The photography in this book is disturbing, showing what happens to Arina in her dreams of Satan. Photographed and illustrated by Karolina Urbaniuk, the black and white photos in this book are of Szasz, wearing the same clothes and hair style but experiencing violence differently in each nightmare attack. Each chapter begins with a photo of Szasz as Arina, featured in a collage of other famous people and common sights in Russia, with a photo of her ravaged body later in the chapter. Each violent photo is accompanied by a paragraph or so of Russian that looks as if it could be from a newspaper clipping. Intrigued, I used Google Image translate and realized the text in those images came from the things Arina says during her attacks.

The photography in this book is disturbing, showing what happens to Arina in her dreams of Satan. Photographed and illustrated by Karolina Urbaniuk, the black and white photos in this book are of Szasz, wearing the same clothes and hair style but experiencing violence differently in each nightmare attack. Each chapter begins with a photo of Szasz as Arina, featured in a collage of other famous people and common sights in Russia, with a photo of her ravaged body later in the chapter. Each violent photo is accompanied by a paragraph or so of Russian that looks as if it could be from a newspaper clipping. Intrigued, I used Google Image translate and realized the text in those images came from the things Arina says during her attacks.

The final attack is, understandably, the one that affected me the most. Arina, wearing the dreaded synthetic leather moccasins she hates, is rushing to a Komsomol Youth meeting where lateness is not tolerated. The bus breaks down and everyone is forced off the bus in the rain and Arina is distressed about potentially being late and in trouble. Chikatilo, who has been stalking her, is on that bus and attempts to comfort her, reminding her that she had no control over the bus breaking down. He urges her to come with him back to his home where she can dry off and wait out the storm, and knowing she absolutely should not follow him, she does anyway, almost fatalistically going to her death. Once she arrives inside the shack, she knows she is in trouble but remains calm, holding onto a sliver of doubt that perhaps this would not end poorly, thinking perhaps she is being too hasty in her opinions. But then it happens and nothing can save her, and in this scene I forgot how obnoxious Arina was, how arrogant and scheming and bratty she was.

She became to me what she was and always was – a teen girl in a dangerous world where terrible things happen to the weak and no amount of pleading or dreams of power could change that.

There are so many ways to explore this novel that I hope others who have read it find this discussion and tell me how they processed it. I cannot say if this is a book you should read, because it is violent and upsetting. However, I can say I found this to be a remarkable book, so remarkable that you may notice by their absence the swaths of text I often reproduce when I discuss books. I did not quote from this book because I have no idea which section would best represent the elements of this book that spoke to me, a former spooky girl who lived in my head and never knew what damage was waiting for me to find it. The entire book is a memory and a revelation to the right reader, and if you are that sort of reader, I highly recommend it.