Book: Sleeping Beauty II: Grief, Bereavement and the Family in Memorial Photography, American and European Traditions

Credits: Stanley B. Burns, M.D. with Elizabeth A. Burns

Type of Book: Non-fiction, photography, death photography

Why Do I Consider This Book Odd: Well, pictures of dead people will always be a little bit odd.

Availability: Published by the Burns Archive in 2002, it can be found from third party sellers on Amazon:

But you can also get a copy directly from the Burns Archive as well.

Comments: As I was poking around in my shelves finding books appropriate for Halloween discussions – books about cemeteries, ghosts, creepy things in general – it struck me how many books I have devoted to death photography. I guess I shouldn’t be surprised. I find death photography absolutely fascinating. The first Sleeping Beauty, purchased from The Strand Book Store in New York for what turned out to be a song, is one of my prized possessions. When I die, I will not leave a sizeable financial estate but hopefully fist fights will break out among my loved ones as they negotiate who gets my Burns Archive book collection.

Mr OTC inadvertently started my obsession with death photography. We had just moved to Austin and he was attending grad school. In one of the libraries someone had removed this book from the shelf and left it on a table. He checked it out and brought it home for me to look through, certain I would be interested in it. How well he knew me even then. I don’t think you can check this book out any more and it took me a very long time to be able to afford the comparatively inexpensive copy I got from The Strand. Now books from the Burns Archive are gifts for me on birthdays and Christmas and that is how I got this copy of Sleeping Beauty II – Mr OTC came through for Christmas in 2006. I wonder if he ever regrets igniting this interest of mine because the books documenting it are seldom cheap. He’d be well and truly screwed if I actually sought out original photos to purchase but I’m a reasonable fanatic.

I find the best way to discuss these books is to quote from the textual information and demonstrate the information with photographs. Because some people, understandably, find pictures of dead children distressing, I will put all such photos under the cut.

Sleeping Beauty II was created…

…to complement the exhibition “Le Denier Portrait” at the Musee d’Orsay, Paris, in which several photographs from the Sleeping Beauty series have been included. This book presents for the first time the important distinctions between American and European postmortem imagery.

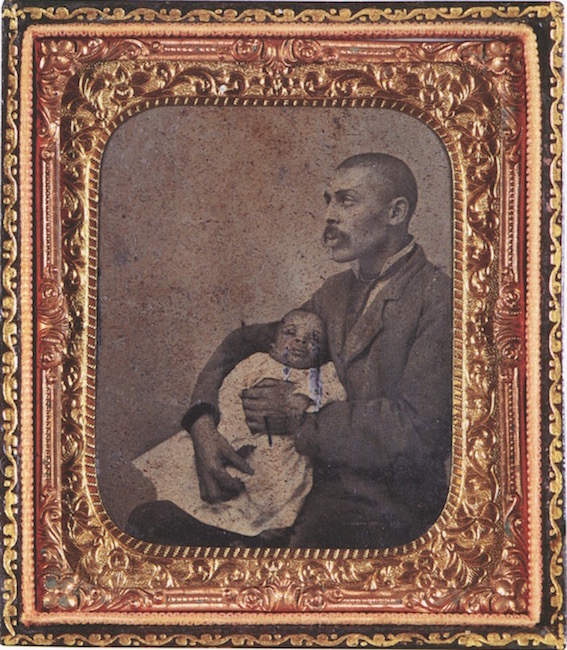

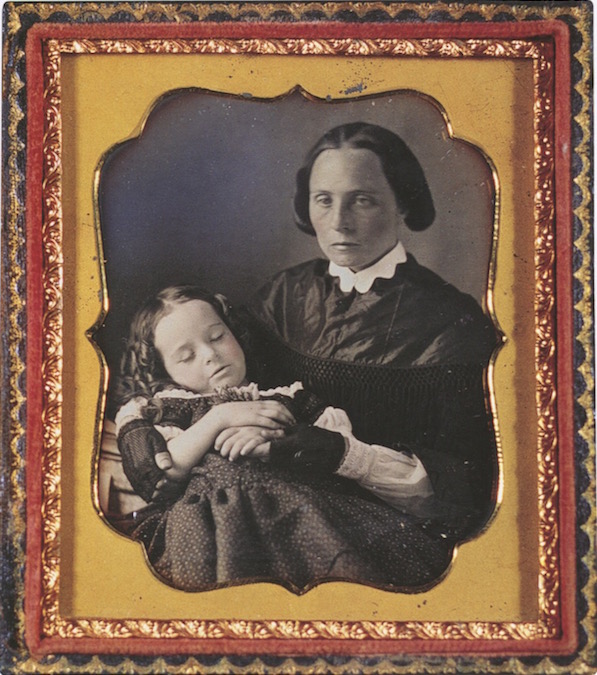

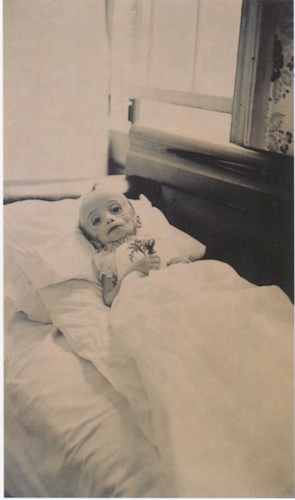

In photography’s earliest years, death was still widely considered a natural part of everyday life. People took photographs of their cherished departed with a reverence little understood today. These photographs were a normal part of the culture, and we are testament to a time when the magic of photography offered the hope of extending relationships. At the moment people who were most vulnerable, photography offered a memento that seemed real – a tangible visual object that allowed continued closeness to the deceased.

We can feel the power of these photographs generations after the images were made. We relate to these pictures of strangers because they speak of a universal language of emotions – tenderness, affection, need, hope, loss and despair – uniting the human family in common experience.

People are often upset by these images and in a way it reminds me of the way people are appalled when some callow youths poses for a selfie with sick or dead relatives. There is something unseemly about forcing the extremely weak or dead into photographs. You can’t be any more vulnerable than dead – you no longer have any control over what is done to you, and it seems foul when some Instagram-generation kid grins next to the open casket, iPhone in hand. But it makes me wonder how such photos will be received a couple hundred years from now. Once we place these photos in the historical context in which they were created, they often seem less callous and exploitative.

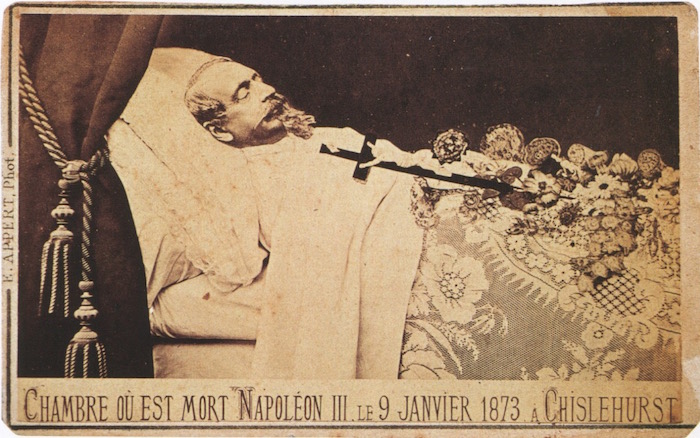

Although Sleeping Beauty II concentrates on American postmortem imagery, it also introduces memorial photographs from other cultures and includes images from fifteen countries. The differences between cultural uses of American and European postmortem photographs are significant. Postmortem photography in America has historically been used for private expressions of personal loss. On the other hand, Europeans often made and publicly displayed postmortem photographs of royalty, nobility, the wealthy and other notables. In America, postmortem photographs of public personalities and political leaders were not taken. These traditions mirror differences in the overall practice of photography on the two continents.

In Europe, early photography was an elitist pursuit taken up by artists as a profession and by the well-to-do as a hobby. In the United States, it was a common man’s trade and could be practiced by anyone, anywhere. As a result, Americans came to expect their pictures to be taken some time during their life or at death.

In the United States, postmortem photography for the middle and working classes ended by the 1930s. However, immigrants who followed the traditions of their countries of origin, as well as populations in some areas of rural America, continued to have professional postmortem photographs taken. In addition, the development of Polaroid instant photography and easy-to-use amateur cameras allowed people to take postmortem photographs surreptitiously throughout the century.

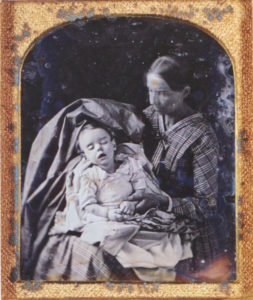

Content, rather than authorship, predominates in these remarkable images. These anonymous photographers, in the presence of death and the sanctity of deep loss, were able to produce captivating images. In many cases, it is quite likely that the families dictated the composition of these scenarios. Though some parents wanted to hold their dead child, others did not – or could not. Art photographers brought their own styles and presentation to memorial images.

As most photographers in Europe came from an artistic tradition, European postmortem photographs followed the styles of deathbed and mortuary paintings. While both European and American families used photography in the mourning process, the traditions of each society dictated presentation and usage.

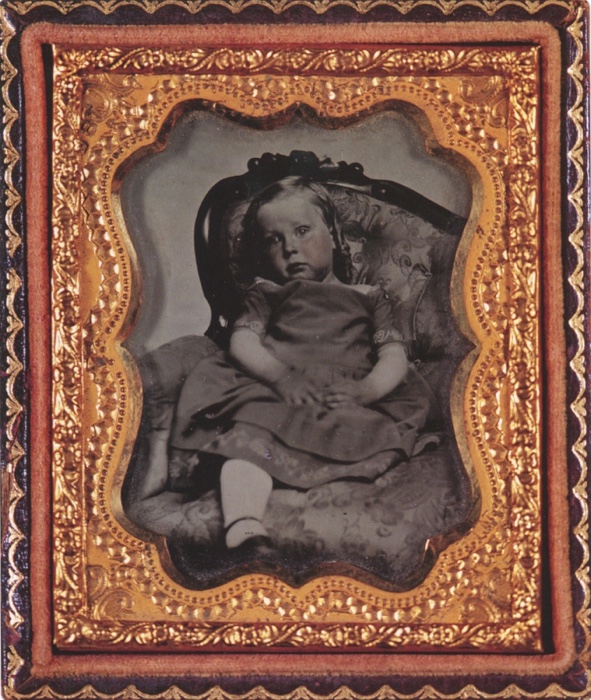

One of the styles of nineteenth century postmortem representation was the posthumous mourning portrait. These images portrayed the dead as if still alive, not simply by having the deceased’s eyes open, but creating a tableau.

During the latter half of twentieth century, most American postmortem photographs were taken privately and kept private. In the past decade, however, public display of these photographs has increased. With widespread acknowledgement of the AIDS epidemic, openly photographing our dead and dying loved ones has become acceptable. Noted photographers and documentary filmmakers have focused on the subject of dying parents and loved one with cancer or AIDS. Photographing stillbirths and neonatal deaths has also become commonplace. Some hospitals are giving one-time-use cameras to parents whose infants have died. Bereavement centers are advising mourners to use such images to aid themselves in the grieving process. Because the range, variety and cultural diversity of the images in this new book allow for individual interpretation, bereavement counselors and their clients may find it a useful visual tool.

Death comes quickly in the nineteenth century. Some diseases could wipe out all of one’s children within a day. Adults too, were susceptible. Cholera epidemics, for example, were swift, savage killers. Curiously, however, except for children who died from dehydration or from viruses that left conspicuous skin rashes, or adults who succumbed to cancer or extreme old age, the dead would often appear to be quite healthy.

When someone dies today, the first thing we do – whether in hospital, mortuary or movie – is close the eyes. In contemporary photographs of the dead, the dead do not stare back. Because of this convention we sometimes fail to realize that nineteenth-century postmortem photographs depict the dead. In the past, families could request that a subject’s eyes be open or closed. In postmortem photography of many children who were never photographed while they were alive, the eyes were left open to provide a semblance of life. This melancholy ruse was sometimes embellished by a tableau that made the child appear to be either engaged in some activity or consciously posing.

It’s inescapable, the sort of cultural rubbernecking that causes me to be so deeply interested in these photos. There is something deeply voyeuristic about these photos, seeing people in the midst of mourning and emotional pain. But these photos are also comforting. The living are experiencing the greatest loss most of us endure – the loss of a parent or child – and they are still standing, engaging in ritual to remember the dead, to make sure others remember the dead, and in the face of death such focus on and sense of duty towards the dead can help even the most modern mind find a way to honor those they lose, even if such veneration comes from simply remembering them when looking at these images.