Books/Authors: The Subsidiary by Matías Celedón and “Wage Slaves” from the Christopher Fowler* short story collection, Personal Demons

Types of Books: Celedón: fiction, art novel, conceptual novel, horror / Fowler: fiction, horror, short story collection.

Why Do I Consider These Books Odd: Celedón’s work is odd because it encapsulates the plot of any number of two hour horror films into one 197-page book that has 1000 words or less, all written with a hand stamp and a pad of black and red ink. Fowler’s work is odd because his early work is so criminally under-known in the United States.

Availability: The English translation of The Subsidiary was published in 2016 by Melville Books and you can get a copy here:

Personal Demons was published 1998 by Serpent’s Tail, and appears to be out of print. You can try to score the occasional used copy here, though frankly I found all of my copies of his older works in used book stores:

Comments: I really adore the work of Christopher Fowler, and he’s a master of city horror, especially the terrors one encounters in office buildings. I don’t recall exactly when I began reading him but I know it was roughly around the time I learned about “sick building syndrome.” Sick building syndrome is the phenomenon wherein accidental design flaws result in very poor air circulation, causing workers to not only spread illness quickly, but also causes CO2 overload combined with inhalation of volatile compounds released by furnishings, cleaners and building materials themselves. That toxic soup leaves some workers feeling ill an hour or so after arriving to work, and the miserable ventilation in modern office buildings demonstrated how sick buildings could fuel contagions of illness, like Covid, due to a lack of healthy ventilation.

Getting trapped in city structures is a common horror trope. P2 tells the story of a woman trapped in a parking garage, and ATM features a trio of office workers who get stuck in an ATM kiosk (both are alternative Christmas movies too, if you’re tired of Die Hard). But in both of those films, the protagonists are stuck because a killer or maniac has decided to entrap them. In a similar vein, 2017 film Mayhem neatly wove disease with authoritarian building lock downs into a building horror when the CDC closed off an office building infected with a short-lived sickness that causes everyone who gets it to become homicidal. The Belko Experiment, also from 2017, is a gladiatorial contest wherein workers are locked inside their office building and forced to engage in murder sprees in order to survive.

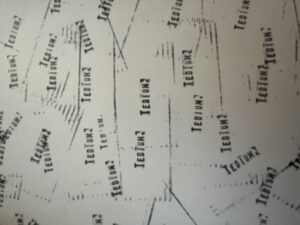

The Subsidiary approaches building horror in the same vein as The Belko Experiment, in that the employees are trapped in their workplace without consent or warning. However, it has more in common with Blindness by José Saramago in that confinement brought out the worst in some of those locked in the building, causing them to prey on the weak. No one knows why the Subsidiary turned off the power and locked all the employees inside, but the Subsidiary ominously warns them that the first lockdown is coming, the Subsidiary takes no responsibility for any damages, and all employees are to remain at their workstations. The darkness begins on June 5, 2008 and ends on June 18, 2008. At the beginning shouting is heard as the power is shut off, the phones killed and the doors locked, but soon it becomes quiet. The first day is filled with TEDIUM and almost predictably, a fly left inside dies.

The Subsidiary approaches building horror in the same vein as The Belko Experiment, in that the employees are trapped in their workplace without consent or warning. However, it has more in common with Blindness by José Saramago in that confinement brought out the worst in some of those locked in the building, causing them to prey on the weak. No one knows why the Subsidiary turned off the power and locked all the employees inside, but the Subsidiary ominously warns them that the first lockdown is coming, the Subsidiary takes no responsibility for any damages, and all employees are to remain at their workstations. The darkness begins on June 5, 2008 and ends on June 18, 2008. At the beginning shouting is heard as the power is shut off, the phones killed and the doors locked, but soon it becomes quiet. The first day is filled with TEDIUM and almost predictably, a fly left inside dies.

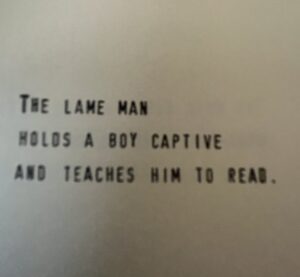

An unnamed clerk in the office uses his stamps and ink to make a record of what is happening to him and his coworkers, who all have names that seem a bit… on the nose. The Mute Girl. The Blind Girl. The Deaf Girl. The One-Legged Man. And so on. After the first day things start getting weird. The Deaf Girl slices his arm and licks the blood. Our clerk is evidently known for his pill habit and his coworkers come to pester him for drugs.  There is very little food.

There is very little food.

Somehow a lost child was found in the building and The Lame Man had to bathe him, whatever that means in an office building with no light or electricity. Somehow he manages to teach the child to read. We later realize that the child really should not be left with The Lame Man, and before long no one is safe from attack. In a terrible sexual attack in the bathrooms, The Blind Girl is left dead. She died naked and is quietly carried away, but soon the men, whom the clerk calls “animals,” come back.

A new order crosses the clerk’s desk because the men are filing a requisition: they’re looking for another girl. A woman near the clerk begs him to save her, whichever woman it is. This image reflects the clerk’s response to her request, and I frankly am not entirely sure what this means. Shortly after the clerk places his stamp on the request, the lights come back on.

A new order crosses the clerk’s desk because the men are filing a requisition: they’re looking for another girl. A woman near the clerk begs him to save her, whichever woman it is. This image reflects the clerk’s response to her request, and I frankly am not entirely sure what this means. Shortly after the clerk places his stamp on the request, the lights come back on.

I bought this book presumably because it seemed to be akin to Christopher Fowler’s works about urban horror. I had no idea it was a conceptual piece more than an actual book. It takes about 10 minutes, max, to read, and it is substantially enhanced by the memory of other works, like the aforementioned Blindness and Mayhem. Because I enjoy the unusual, I wasn’t put off by the fact that this somewhat pricey hardcover turned out to be an art experiment in story-telling using archaic office stamps, but I can imagine that this book requires a very specific kind of reader to enjoy it.

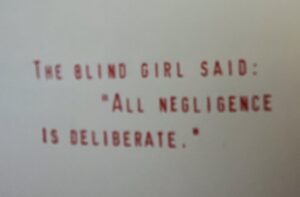

Even though I took the concept in stride, there is an interesting problem I had with the book. The use of the rubber stamps necessitates truncated story-telling, but the story being told is very expansive, including a section that causes the reader to wonder if any of this is really happening because the clerk may be a very unreliable narrator. This concept would have been far more effective had it been stamped into stony reality, using this unusual method of story-telling to make a specific and unwavering point.  The almost-allegorical use of descriptive names also signals something that I don’t entirely pick up on because there simply is not enough in the book to explain why it is that these names signify something particular about the person. In such a heavy story, these nursery-rhyme names surely have meaning and it’s irritating that I don’t know what they signify. Add to this that there are so many high-minded utterances like “ALL NEGLIGENCE IS DELIBERATE” makes it all the more almost pointlessly artistic. And these last few sentences may make it seem like I didn’t enjoy the book, but I did find it interesting. Sometimes a fresh or ambitious approach is itself enough to praise (however faintly) a book.

The almost-allegorical use of descriptive names also signals something that I don’t entirely pick up on because there simply is not enough in the book to explain why it is that these names signify something particular about the person. In such a heavy story, these nursery-rhyme names surely have meaning and it’s irritating that I don’t know what they signify. Add to this that there are so many high-minded utterances like “ALL NEGLIGENCE IS DELIBERATE” makes it all the more almost pointlessly artistic. And these last few sentences may make it seem like I didn’t enjoy the book, but I did find it interesting. Sometimes a fresh or ambitious approach is itself enough to praise (however faintly) a book.

Personal Demons is far more accessible and far less ambiguous, which may seem like points against its favor, odd-wise, but Fowler’s impeccable characterization and creation of technological ideas that seem possible even though they are from the not-too-distant-future more than make up for a lack of outright oddness. “Wage Slaves” tells the story of Ben Harper, a disgraced 26-year-old teacher (he encouraged his students to engage in protests that were categorized as “insurrection”) who falsified his CV so he could get a corporate job, and his realization that his new office is probably going to kill him.

His possible death is foreshadowed in the first few paragraphs of the story, but at that moment the reader does not know yet why Mr Clark, the head of PR, has beaten his subordinate, Mr Felix, to death with a cricket bat. He could just be a garden variety corporate psycho. But it doesn’t bode well for Ben.

Within an hour of being on the job, a co-worker named Marie, who had been canoodling with the late Mr Felix, pegs Ben as a poser with no corporate experience. She blackmails him into meeting her for lunch on pain of her telling everyone he is a fake. Marie is very concerned that there is something wrong at her place of work, Symax, whose motto is “the future is now.” She takes him to a restaurant outside of the building because everything done inside the Symax building is recorded and can be used to fire them. Or worse.

Poor hapless Ben who just wants to keep his new job of a few hours, is openly dismayed that Marie is dragging him into a potential conspiracy. Over lunch he passively pleads for her to back off.

“The secretaries are always off sick. They say there’s something in the air that makes you ill. At this height the windows can’t be opened because of the wind. Then there are the phone lines. They randomly switch themselves around like they’ve got poltergeists or something.”

“It’s my first day,” he pleaded.

“The staff can sense that there’s something wrong even if the management can’t, but no-one – NO-ONE – is willing to talk about it.”

“The suit is brand new, Marie. And the tie.”

Mr Clark quickly becomes suspicious of Ben. It hardly matters that he and Marie met outside the building because the office monitors everything and soon it is clear Ben is snooping around.

Mr Clark glowered at him. “I don’t like you, Harper? Why is that?

“You haven’t tried my cooking yet?”

The rest of the office receives an email warning them about Ben but it speaks to the increasing chaos inside Symax that no real action is taken. What Ben discovers about Symax is unnerving. Symax’s headquarters is a “smart” building. It reacts instantly to all input, attempting to keep a continual state of static equilibrium. Doing so creates constant change. For example, if clouds pass over the sun, the building immediately brightens the indoor lights, which causes computer screens to adapt their brightness. This is one small chain of events to keep the building in a specific state of being perfectly lit. Imagine all the chains of events needed to keep the place clean, temperate, with moderated sound and so on. Even empty the building would be constantly working to overcome any deviation from its main programming objectives.

But what happens when you add people to the mix? Well, as the architect of the building explains to Ben:

“A building is not just a box made out of bricks. It’s organic. Shaped by the needs of the people within. This building responds. People cause disorder, no matter how well controlled they are. The Symax system is responding to human chaos with counter-balancing chaos. Action, reaction. People break down – what happens to buildings?”

Mr Clark, who was a career asshole before the continual electromagnetic shifts in the Symax building exacerbated the worst of his tendencies, eventually fires Ben, but not before dragging out of Ben the reasons why a man so desperate for work that he would lie about his experience would so quickly trash the opportunity by becoming a spy for a disgruntled coworker.

Ben thought for a moment. “Human nature.”

It would have been better for Ben had Mr Clark fired him a couple of days earlier. Mr Clark had the entire company working non-stop and overnight for a big deadline and the building had gone as insane as the people inside of it. Clocks ran backward, Biro pens spun clockwise when placed on their sides, water coolers created typhoons inside the plastic until it exploded, and the electronics that controlled the place began to malfunction in such a way that the electromagnetic waves caused an executive to swan dive out of his office building window while other people had complete nervous breakdowns.

Never fear, though, the smart building has a smart solution for when things get as out of control as they were getting at Symax. Fowler leaves the gory details to our imagination.

I’ve always maintained that I am not as visually oriented as I am a fan of the word. I can appreciate the experimental, artistic nature of Celedón’s building horror, but appreciate more Fowler’s humorous attempts to demonstrate the real horrors of working in a closed off space with a lot of unstable people. All that’s missing in the real life office is the sentient building waiting to correct everything, but then again I have not worked in an office in a very long time, so maybe we’re closer to experiencing Fowler’s dystopian office building than I know. All I know is I’m really suspicious of that Alexa things.

I’m glad I don’t have to deal with offices anymore. I had a fear of door handles that predated the fear of fomites Covid brought us temporarily. People are gross, and it’s daunting being around them in poorly ventilated spaces where the windows can’t be opened and there is a heavy reliance on elevators. Christopher Fowler neatly pokes at this nervous fear of contamination and confinement very well in his urban building horror, and that’s why his work is so effective for me. His short stories take the tiresome nature of grocery shopping, the worries of what you may really be eating when you order fast food, the potential for use of little nooks and crannies in downtown buildings, things so many people in the West experience daily in our lives, and reminds us that so much can go wrong in our orderly lives and how there is still the potential for discovery in even the busiest cityscape.

Celedón’s work is probably only worth it for the story if you can get it on sale, though people into interesting artistic conceits may disagree. Fowler, however, is worth it for me at any price. Unfortunately so much of his work is out of print, especially his early short story collections, like City Jitters, The Bureau of Lost Souls, and Sharper Knives. If you are a fan of that sort of humorous, witty, familiar horror, Fowler’s early works may delight you as much as they did me. He can also slide into deep human emotion, dabbles at times in deep horror and gore, and handles body horror in a way that still haunts me to this day. Grab his work if you can get it.

Do you have any building horror pieces that you enjoyed? City terrors? Share. And if you’ve read any Fowler, let me know what you think of him.

*Christopher Fowler died in early March, 2023. I’ve been more or less offline for five years, and am filled with regret that I never interacted with him on his blog or on Twitter. He was a kind, funny, accessible, extremely talented man, and one of the best horror/mystery/slipstream writers of the late 2oth century and early 21st century. I need to write about him more in the future. His memoirs will be published posthumously and I’ll be sure to discuss it here, whether it’s odd or not.