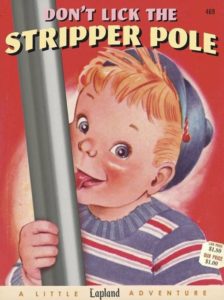

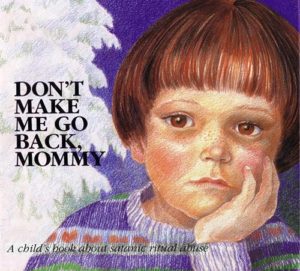

Book: Don’t Make Me Go Back, Mommy: A Child’s Book About Satanic Ritual Abuse

Author: Doris Sanford, illustrated by Graci Evans.

Type of Book: Children’s book, illustrated, utter fiction

Why Do I Consider This Book Odd: Well, it’s no My Friend, The Enemy: Surviving Prison Camp, but it has its moments. Also, discussing the background of this book takes up much more intellectual space than the book itself.

Availability: Published in 1990 by A Corner of the Heart, it’s out of print, but if you have money to burn and enjoy that sickening feeling you get when you realize you have a relic of an entirely different form of child abuse than the book professes to tackle, you can still get a used copy on Amazon. However, the book is so reviled that Amazon will not permit me to link to it directly.

Comments: The late 1980s and early 1990s were a weird time. All over rural and suburban America, white people became very afraid of Satan, and sometimes even “real” Satanists participated in the freak show of Satanic Panic. Some of us listened as Bob Larson, huckster and self-taught exorcist, attempted to exorcise demons out of Trey Azagthoth, from the death metal band Morbid Angel. Glen Benton, front man of Deicide, spent a lot of time taunting Bob, and frankly that time could have been better spent injecting heroin straight into his balls, but, like I said, it was a weird time. Geraldo, Sally Jesse Raphael and Oprah had the pre-cursors of soccer moms convinced that Satanist wolves infiltrated every corner of the planet – but mostly white, middle-class pre-schools, it seems – in order to pass as sheep, ready to savage their children.

It was a very dark time, my sarcasm aside. Families were destroyed because poorly trained and dogma-afflicted therapists and hysterical, mostly fundamentalist Christian, parents believed children could not be led into making up salacious details about abuse that never happened. They believed children when those children, after hours and hours and sometimes days and days of leading and suggestive comments, told impossible stories about abuse that they claimed was heaped upon them at day care centers. The McMartin pre-school case is one of the best examples of the Satanic Panic run amok.

A mother, whom members of the community later admitted was utterly unstable and had a history of making false accusations, was convinced that Raymond Buckey, son of the owner of the McMartin day care center, had sodomized her son. She went to the police during a time when law enforcement was willing to believe such claims without much in the way of evidence, and during the investigation letters were sent to parents of children who attended the day care, asking them to check with their children to make sure Raymond hadn’t, you know, raped them repeatedly. Predictably, parents became hysterical and some of the most poorly trained therapists ever to worry about men in hoods in the woods pressured McMartin attendees until they remembered any number of absolutely impossible situations, involving every McMartin employee, as well as random strangers unlucky enough to be lumped into the group of suspects.

McMartin kids, under the questioning of a therapist who really needed there to be a terrible scandal and shaped one that fit neatly with her bizarre beliefs, insisted that sometimes they were flushed down toilets into tunnels under the school and used in Satanic orgies. They claimed they saw lions and horses killed, as well as rabbits being frequently killed in front of them to make them compliant. They claimed they watched as babies were sacrificed at the local Episcopal church. They claimed Raymond Buckey could fly, that they were filmed naked and their abuse was taped as a game the adults called “naked movie star.” Nary a photo or film clip was ever found. It never really seemed to register with the therapists involved that something was wrong with all these weird stories, not even when kids could not identify Raymond, their supposed rapist who flew and killed rabbits, but did identify Chuck Norris as one of the men who harmed them. No one felt a bit unsettled when the kids spoke of being taken from abuse locations in hot air balloons, or that the kids were taken to cemeteries during the day and forced to dig up corpses, which their day care instructors began to stab repeatedly, hacking the bodies up before forcing the kids to rebury them. Even more bizarre physical evidence was used to prove the accusations of kids who had no physical signs that they had been abused, let alone repeatedly raped, cut, or beaten. The now utterly debunked “wink” anus test was used on little kids, and as a result those little kids ended up being sexually abused by the people set on saving them from abuse.

That’s a problem that comes up a lot in Satanic Panic cases – if the kids weren’t victimized by those accused of abuse, the accusers put the kids through such nightmarish questioning and physical examinations that they were definitely victimized. Some of the McMartin kids have grown into adults who believe the system failed them, permitting the people who sacrificed endless numbers of babies to Satan while raping them and their friends to eventually go free. They feel traumatized and victimized and their lives have been ruined. While a lot of people look at this kiddie book as a real life example of Liartown’s fine book parodies…

…it’s only funny if you don’t know the truth behind it.

As I type this, I know people who really are into Dave McGowan’s Programmed to Kill, the belief that Bush the Elder led a pedophile cult that preyed on kids involved in the Franklin Scandal, and every minute detail from the whole of the recent Pizzagate weirdness are going to come call me a black propagandist, insinuate I get paid by the Podesta brothers to write such articles or accuse me of being a pedophile. Same as it ever was. Every such commenter reads a refutation of their hobby horse and feels it is an apologia for child abuse as a whole when it’s really just other people questioning their intellectual fitness. It makes me glad this book is out of print. Perhaps it’s best they waste their time leaving me silly comments because otherwise they might actually engage in real life advocacy and no one, especially children, needs that.

Now to the book.

Don’t Make Me Go Back, Mommy is a direct response to the McMartin pre-school case. It even brings up the game “naked movie star.” (The key, or should I say “Kee,” therapist involved with the McMartin case, took a slightly bawdy rope skipping chant and turned it into a tacit admission of kiddie porn involvement – “What you say is what you are, you’re a naked movie star!” Our weird chant when I was a kid was a vulgar variation of the song “Tah rah rah boom dee-ay.” We all had them but, again, it shows a lot about the mentality of the professional adult who immediately believes such silly rhymes mean kids are being gang raped.)

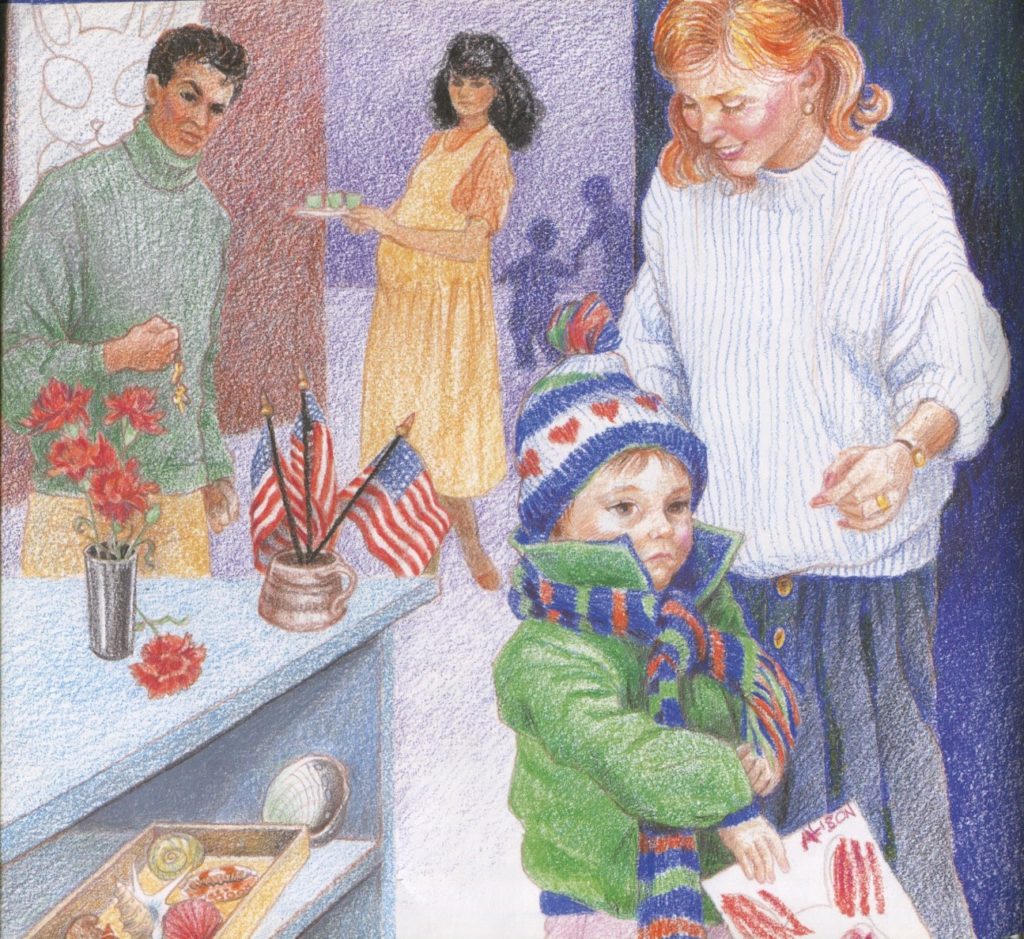

The story is pretty basic – little girl gets Satanically abused at her day care, she tells her parents, who work hard to help her recover, and assure her that God was really sad she was abused.

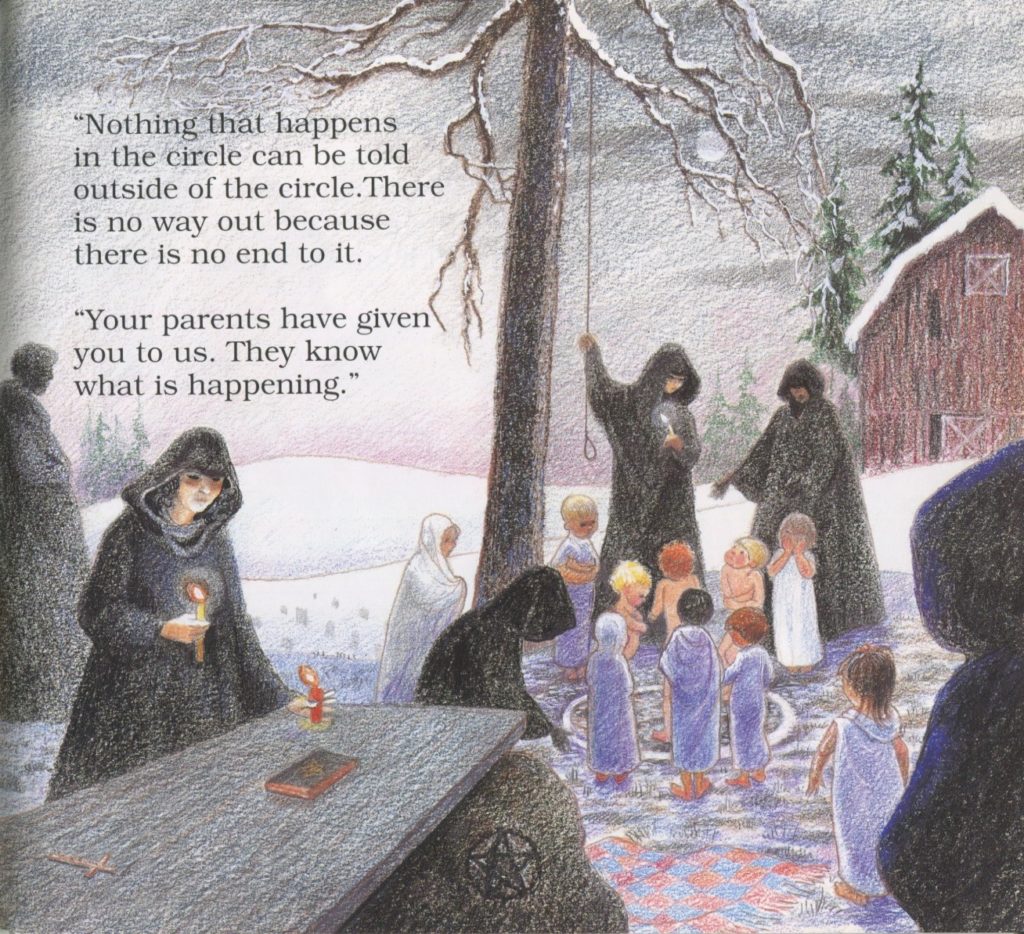

The illustrations in the book are drawn by Graci Evans and they do a decent job of revealing some McMartin realness.

I’m unsure what to think about Doris Sanford. I can’t really find much information about her, aside from basic obituary-level information – she appears to have died in 2018. She began her foray into self-help books for kids by discussing the impact of parental depression on kids, and how hard it is for kids to process death, both helpful and useful books. Even her books about sexual abuse at home seem charmingly helpful in comparison to Don’t Make Me Go Back, Mommy. But over time her titles became more… upsetting. How many kids were out there who survived death camps and also had access to American book stores? The kids in Rwanda weren’t gonna see Doris’ book about death camps, nor were kids who suffered in the Balkans. But she wrote a book about it. And she wrote this book, and no matter what alarmists tell you, Satanic Ritual Abuse is rare and hardly has an audience large enough to support a book helping the children who survive it.

Was Doris a True Believer in Satanic Panic? Was she jadedly making a buck off the backs of people who were clearly already willing to torture their kids? I have no idea. Worse, her book may well have been the lesser of several other evils. I remember a woman on my street when I was a kid who would give out Jack Chick tracts and a dime to each kid on Halloween. My mom made me go to her door each year that I trick-or-treated because she wanted to see what lunacy I’d walk back with. I lack the will to look up the exact title, but I remember one year I got a tract about how some kid died and when he went to heaven God showed him every terrible thing he’d done on some sort of celestial slide show projector, and I began to worry if my mom was trying to tell me God had a rap sheet on me a mile long and I needed to get my shit together. Really, she just wanted to see what crazy crap the woman was giving out that year. But I remember being very upset that God had basically set up surveillance on me and was collecting evidence of every sass back, every lie, every thing a child does because she’s a child, in order to shame me when I died. At least Doris’ books had decent production values.

So I guess what I am saying is that people love witch hunts and that will never not be true, and every generation has their own unique way of terrifying kids with images of Satan.

But this book, all kidding aside, is an excellent relic of the time that spawned it. And for all I know it was a legitimate and sincere attempt to address what at the time seemed like a terrible societal ill. But the utter perversity of the accusations, the beliefs people had about well-organized cabals preying upon the most privileged and well-protected children in human history, shows a sort of sickness within that even now people don’t like to address. What do you do if your mother is certain you were sodomized in a tunnel by an American icon like Chuck Norris, who most definitely did not have large chunks of time he could be away from film and TV sets to hang around in subterranean lairs to rape toddlers? How do you cope with the rectal exams you were forced to endure because adults really believed you were taken away in hot air balloons to be raped in the Episcopal church? What does that say about the secret fantasies and moral bruises of those who believed such unbelievable, foul, bloody and sexually perverse things?

I have an answer of sorts in a film I will discuss tomorrow, an animated film inspired by this specific book. See you then.