Book: In Full Color: Finding My Place in a Black and White World

Authors: Rachel Doležal and Storms Reback

Type of Book: Memoir, political biography, fraud, race issues

Why Do I Consider This Book Odd: I mark up books as I read them so I can discuss them and seldom does my opinion of a book or its subject change when I review those notes. My first read-through of this book I had a certain amount of sympathy for Doležal but when I went back over my notes I felt my sympathy fading. It’s almost like I experienced the ruse via her book – I saw what she wanted me to see initially but when I looked at specific statements by themselves a completely different picture emerged.

Less analytically, this book is odd because it’s written by a woman who claims she is “transBlack” and became a national disgrace for her efforts.

Availability:

Comments: When I learned Rachel Doležal had written a book I knew I was going to have to read it and discuss it in depth. Because she’s rather topical at the moment, I worry discussing her will attract readers who are unaccustomed to the nature of this site. I’m a person who writes, using far too many words, about things I find interesting and those things are often odd. This site is mostly devoid of any political agenda, though I’m sort of a liberal, and I am looking at Rachel in terms of what she wrote in this book. All political and social reactions I have to Rachel in this article are fueled by the text of her book, though I will use outside sources to bolster some of my own assertions.

Rachel Doležal has been all over the news again recently and I’ve done my best to avoid reading too much about her – even when an author or person I discuss here is currently in the headlines, I still prefer to analyze their work without a lot of outside influence. I’ve stayed away from her television appearances and have especially stayed away from The Stranger article about her (the buzz around it is killing me but I will remain strong until I’ve got this series finished). I’m at my best when I’m not influenced by other people’s opinions. This is going to be another one of those articles I’m known for – going deep into a text while everyone stands back and tells me, “I don’t even know why you’re giving her this much attention, that’s what she wants!” Yeah I know but this is what I do – I pay lots of attention to things other people may think unworthy of such focus. . Only my discussion on Anders Behring Breivik, the Utoya shooter, is longer than what I have written about Rachel Doležal. I have no idea what that may mean other than that I find her very interesting.

So I read the book closely and I tried to research as much as I could about some of her more controversial claims. At times verification was impossible and given that this is a book written by a serial liar and fantasist it’s hard to put much faith in anything Rachel says about her life. I had to make what may seem like arbitrary decisions about what I choose to believe is true and what is more self-serving deceit.

It’s hard to make such decisions at times because I don’t think Rachel Doležal is wicked or evil in a calculated way. She’s just a self-centered, delusional, holier-than-thou, condescending woman who took her shtick way too far and refuses to back down, rethink, regroup, and move on.

There are several reasons why I initially had such intense sympathy for Rachel and part of that sympathy was fueled by distaste for many people who have gone after Rachel on social media. I was particularly interested in the transexual communities’ responses to Rachel and was shocked by the amount of paranoia some transfolk felt toward Rachel as well as some of their violent rhetoric. I was also ultimately concerned about the outright hypocrisy I found – it took less than ten minutes on Google to find out without any shadow of a doubt that one of the shrillest voices yelling online about Rachel belonged to a white man who was himself assuming a false identity. So ridiculous and egregious is his ruse that I wanted to out him but decided against it because I find doxing distasteful and because, like Rachel, he is so unpleasant as a whole that he is self-quarantining. If he ever shows up in public trying to affect social justice while wearing his disguise I may reconsider but for now I’m not interested in poking him with an e-stick.

Rachel is no different than any other liar or fantasist. People who wear a mask and engage in personality fraud on this scale have two interesting issues at play, and initially they may seem contradictory: self-loathing and a sense of superiority. Such people feel they are the smartest and most competent person in the room yet lack the ability to persuade others of their superior skills and knowledge. They can’t endure the ego blow that comes from criticism and do anything they can to avoid it. If persuading others they are correct and avoiding criticism can be mitigated by lying about their pasts or creating a persona that to some degree shelters them from criticism, that’s what they do. But as they talk about themselves they always reveal their true selves. This book is chock full of the real Rachel Doležal and, like other serial fantasists discussed on this site, she has no idea what she’s revealed about herself, so focused was she on perpetuating the notion of herself as a blameless victim.

This book was such a bad idea. Even with a co-author, Rachel Doležal shares so much negative information about herself, information she doesn’t seem to understand is negative. I’ll show you exactly what I mean, using plenty of quotes from the book, occasionally linking to information online that helps gives perspective to the stories Rachel told about herself and others.

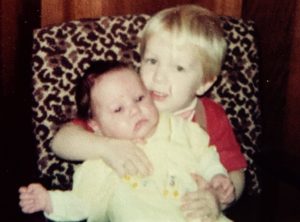

But before we begin, a quiz. Which of these two white girls born in the seventies is Rachel Doležal?

A: The girl on the left

B: The girl on the right

C: Trick question, one of these girls is clearly a black child!

D: All of this makes me very uncomfortable.

Because this is a long discussion broken up over several entries, I want to give as quick a synopsis of the content of this book as I can before I begin to dissect the text: Rachel was born in 1977 to a Pentecostal, very traditional family. Her parents lived a poverty-level lifestyle by choice and Rachel and her older brother, Joshua, were both overworked to help maintain the household. Rachel felt very hemmed in by the overwork and the religious dictates of her very strict parents, dictates that often spilled over into abuse and cruelty. Rachel also accused her brother of sexual abuse.

When her brother left for college her parents decided to adopt four black children, and Rachel, who was home schooled at the time, took on the brunt of much of the child raising and ended up closely bonded to the children. The adopted children’s time with the Doležal family became difficult and marked with terrible abuse when they got older. Rachel left for college herself when they were still small children, got her undergraduate degree, than received her Master’s degree from Howard University. While at Howard she got married and had her first child, Franklin. She relocated to the Pacific Northwest and eventually left her marriage because her husband was controlling and abusive.

Forced to remain in the Pacific Northwest due to custody issues with her son, Rachel tried to establish a new life. She dated men and women and slowly transitioned into living her life completely as a black woman. She held various positions with universities and civil organizations in Idaho and Washington and was teaching part time at two universities, serving as an ombudsman to the police force and was Spokane NAACP chapter president when she was outed as a white woman. Her adopted brother Izaiah came to be legally her son after she gained guardianship of him, and her sister, Esther, came to live with her when her high school courses were complete. Esther revealed that Joshua Doležal had also molested her and Rachel supported her decision to try to bring charges against Joshua.

After the news about her true race broke, Rachel hit the talk show circuit, discovered she was pregnant and decided to have the baby, a little boy named Langston. Then she wrote this book and here we are. Contrary to what some people may think, Rachel earned very little money through her lies and the power she wielded was very limited and local in its scope. Ultimately she set so many teeth on edge wherever she went that she sort of marginalized herself.

I think this in depth discussion is necessary mainly I want to write about the book but also because a lot of people have opinions about Rachel but actually know very little about her. We just know we’re supposed to hate her. While this discussion is very long, it’s way shorter than reading the whole of this book so if you are curious about Rachel but don’t want to read this book, consider this a public service.

I also think it’s important to see how Rachel came to be how she is. There has been a lot of discussion about how she comes from a white family but little conversation about the family itself. This first installment in The Rachel Saga is not any sort of apologia for her behavior but it is helpful to know how she ended up this way. Few of us just happen – most of us are made, all apologies to Mark Twain. Rachel started from a bad place and developed some very maladaptive coping skills. Her childhood, I think, is primarily why I felt such pity for her initially and I still have pity for her. Fundamentalist Christianity has a lot to answer for and none of us risk anything by having empathy for the ill-used little girl who ended up becoming the woman who is a laughingstock.

Please be aware Rachel capitalizes black as “Black” in her book, which I replicate faithfully in quotes from the book but will not adopt in my own writing. Also, due to various financial shenanigans her parents engaged in at her expense as well as the overall abuse of her childhood, Rachel has disowned her parents and calls them by their first names: Larry and Ruthanne.

…I grew up in a painfully white world, one I was happy to escape from when I left home for college.

I can anticipate all the world’s tiniest violins playing for Rachel’s childhood because many people live through horrible times when they are kids and don’t rob banks, turn to drugs, or impersonate black women for fun and (very little) profit. But some of us do end up criminals, addicts or frauds. Other people’s rectitude in the face of hard times doesn’t rob misery and abuse of their erosive power on the human character.

Quickly, on the subject of believability: Rachel is a liar but her biological brother’s own writing backs up many of her stories. He was especially appalled by her treatment in her marriage. As for the sexual abuse accusations against Joshua Doležal, I am less certain but his two sisters both accuse him of sexually abusive behavior, he was arrested and was set to go to trial before Rachel Doležal was revealed as a fraud and the case was dropped. Authorities don’t like to go to trial unless they think they have a fair chance at winning so someone in the legal process found merit in the claims against him. I am not a fan of “listen and believe.” I’m a much bigger fan of “listen and take seriously” and I am taking that approach with the claims against Josh Doležal and I simply don’t know the truth. You will need to determine how you think about Josh Doležal on your own but for the purposes of this discussion I am proceeding under the belief his sisters told the truth. So with this qualified level of belief in the facts of her childhood and Rachel’s own reactions, let’s look at her childhood.

That Old Time Religion

Ruthanne Doležal, Rachel Doležal’s mother, hailed from a family that were part of the Assembly of God branch of Pentecostalism, and Rachel mentions her parents were a part of the Jesus Freak movement as well as being Young Earth Creationists. Assemblies of God is no worse than many other fundamentalist religion in the USA, but certain branches of fundamentalist Christianity tolerate all kinds of ills. Elements of the childhood Rachel describes sound to me like the wretched horrors that describe the physical abuses advocated by Michael Pearl and No Greater Joy Ministries, the ethnic baby collecting and abandonment of extremist fundamentalists like scary Nancy Campbell and her daughters in their creepy Above Rubies ministry, the poverty advocacy of some fundamentalist branches that force families to rely on child labor to survive, and the willingness to sweep sexual abuse under the rug at the expense of the victims.

Jesus Freaks seem kind of benign in retrospect but they spawned seriously frightening cults that engaged in sexual abuses. For every hippie Pentecostal living communally and praising Jesus as they beaded macrame you ended up with people in Children of God cults preying sexually on children and various survivalist death cults that ran into the wilderness to await the end of times. Rachel’s experiences straddle several elements that skeptics find troubling with some branches of Pentecostalism, fundamentalists in general, Jesus Freaks and other similarly religious sects that are cultish in nature.

The patriarchal elements of fundamentalism set Rachel up to be subservient and deferential to men. Her body was not her own, her time was not her own, her life was set up for her to be of use to others without much notion of what she wanted. But even as I state these religious harms, Rachel had certain freedoms that many girls in deeply fundamentalist homes lack. Still, I can’t imagine many women would escape such a family and upbringing unscathed.

The Curse of Ham

Psychologically, Rachel felt like a burden from the very beginning. Her mother gave birth to Rachel unassisted and almost died.

I would continually be reminded throughout my childhood just how difficult my delivery had been for my mother. That I’d nearly killed her weighed me down with a sense of guilt I could never fully shed.

She felt she never measured up to her older brother, Josh.

It quickly became clear to me that in our family, Josh was the blessed child, while I was the cursed one.

That’s a common feeling among girls raised in fundamentalist families – the boys are more favored than the girls.

But this feeling of being cursed took Rachel to interesting places mentally.

The idea that Black people are victims of the so-called Curse of Ham, that they actually deserve to be treated poorly, remains embedded in our collective psyche to this very day.

That I, too, was somehow cursed was imparted to me before I could even speak. I’d nearly killed Ruthanne as she’d labored to deliver me. That my hair at birth was almost black and my skin was much darker than my parents’ and my brothers’ was a great source of anxiety for Larry and Ruthanne and added to the notion that I was the lesser child in the family.

Keep in mind that the picture Rachel uses to show how much darker she was she was shows she was a pink, chubby baby – hardly dark skinned at all – and her perception that she was far darker than her family as a baby will come up again.

It’s hard to know if this was really an issue in her family or one she retrofitted to justify her attraction to black skin, but Josh’s descriptions of his own childhood make me believe Rachel did feel herself to be accursed.

That curse of stained skin became worse after an incident of sexual abuse. I do not want to quote the passage but to give background Rachel and her brother were processing huckleberries for eating while their parents were out and filial teasing and throwing berries at each other got out of hand.

I ran to the bathroom and cried. When I returned, I couldn’t look at Josh. I could only stare at the purple stains on the dining room’s white walls, where the huckleberries we’d thrown had splattered. I felt numb, but I knew that if Larry and Ruthanne saw those stains Josh and I would be severely punished. Expecting them to return home any minute, we worked together to clean up the stains, but they wouldn’t come off the walls, no matter how hard we scrubbed. Finally, in an act of desperation, I rifled through one of the kitchen drawers, found a bottle of Liquid Paper, and used the miniature brush attached to the underside of the cap to apply several coats over the stains on the wall, finishing just as Larry and Ruthanne pulled into the garage.

The stain left upon my body and mind by the events of that evening has been much harder to remove.

Though Rachel gives a lot of lip service to how much she loves the sass and power of the black race, she also thinks of it as a group of people she felt embodied the impact of enforced toil and ill-use.

Rachel’s Inner and Fantasy Life as a Child

Rachel and Josh were both overworked as children, to the point that little Rachel identified with slaves.

As I learned about U.S. history in school, I empathized with those whose free labor helped build this country.

This mentality stayed with her even through her teen years. Here’s how she felt about being sent to work for a friend of her father’s one summer (and she is referring to The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman):

Because the narrator is a 110-year-old Black woman, I would never know what it was like to walk in her shoes, but I could still relate to aspects of her struggle. I certainly wasn’t enslaved, as Miss Pittman had been as a little girl, but it wouldn’t have been too much of a stretch to call me an indentured servant to the Morgans (and to Larry and Ruthanne before them). I was dependent upon them for the food I ate and the bed I slept in, and if I quit working for them before I fulfilled my obligation to them, I’d have no way of getting home.

This melodramatic way of thinking is not uncommon for teenagers but when Rachel was younger her ways of thinking were understandable because she and her brother indeed worked far more than the average child. You read enough about fundamentalist families and this becomes common – the amount of work some of these children are expected to do is staggering.

Rachel describes a household chore schedule that sounds like a Victorian under-maid crossed with a scullery maid and a gardener, and she kept up very high grades in school while playing extracurricular sports (she eventually quit softball because she was accustomed to wearing dowdy garb and skirts and felt horrified in the tight leggings she was asked to wear when she played catcher). In addition to all of this effort, Rachel created art and wreathes to sell at craft fairs and canned preserves to earn money. She even launched a small lollipop company.

By the time I was nine years old, I was paying for all my clothes and shoes.

This may sound outrageous but I believe it because I too was earning the money for my clothes and school lunches when I was in grade school. I crocheted little bookmarks called “bookworms” to sell and cleaned houses, including the houses of the elementary school secretary and principal. Rachel explains that earning money also carried the hope that she would gain some ground in convincing her parents she was worthy of love. Unfortunately, I understand this mindset, too.

When her parents decided to adopt four black babies back to back to back to back, Rachel had already transitioned to home schooling and became a second and at times primary mother to those four babies. Her life in Troy, Montana living with her family was a blur of work punctuated with shame and misery. So it’s not surprising Rachel descended into fantasy life to distract her from the tiring boredom and drudgery she felt. She enjoyed gardening the most of all her chores because it allowed her the quiet and the space to engage in a fantasy world.

In my fantasy, Larry and Ruthanne had kidnapped me, brought me to the United States, and were now raising me against my will in a foreign land.

These fantasies helped Rachel separate mentally from her unhappy life.

I would soon come to accept that I hadn’t actually been kidnapped and taken from Africa and that I wouldn’t be free of my family anytime soon, but the feeling that I was somehow different from them persisted.

Most creative, intelligent girls would feel very thwarted in such a family but Rachel did not have much access to other girls her age who also lived like her. Her deeply religious upbringing, dowdy clothing and very long hair made her feel alienated from classmates to the point that she decided home schooling would be easier than the struggle between the secular and religious world. She was very isolated and her inner life created a wall between her and her family.

…I would often imagine I was an indigenous person, gathering food for the winter. My previous fantasy about being a Bantu woman living in the Congo often returned. I imagined I was an only child, and my mother was ill or dead, and I had to dig up enough cassava to feed my entire family. These fantasies came easily, left just as quickly, and helped me get through grueling thirteen-hour workdays while making my back and neck hurt a little less.

Rachel’s father was careless with her physical and emotional well-being. On one berry picking expedition (which sounds cute and bucolic but was a back-breaking chore that earned money that was substantial for a family living so close to the bone), Larry Doležal decided that if wild goats could balance on a mountain ledge, so could he and his daughter. Clutching the basket of berries, Rachel was terrified she would fall to her death and could barely move. When her father made it back onto level ground he told her she had half an hour to work her way off the ledge and make it back to the truck and if she was late he would leave without her. Of course Rachel made it off the mountain ledge but she never got over the callousness.

The “Little Gang”

Rachel insists that her parents adopted four black children – all from different families, one from Haiti, all babies close in age – because losing Josh as a tax deduction was devastating to them. They opted for black children when they realized that adopting a white child would be very expensive and would take longer. They brought these black children into a family environment wherein they knew the children would be marginalized. Ruthanne’s father began to cry from shame when he first set eyes on Ezra, as he realized his adopted grandson was black.

Larry and Ruthanne received a lot of social capital from their religious community for adopting black children, so much so that they eventually joined a ministry with the children in tow to tout their ideas of good works in other countries. They did not seem to have much love or respect for their adopted children and their treatment of these children greatly influenced Rachel. Her fantasies about being an African orphan became less frequent as she saw the reality of blackness in the United States.

With four Black siblings and two white parents, I was now living in a home that was Blacker than it was white. Some of my relatives began referring to Larry and Ruthanne as “colorblind” and “cultural revolutionaries” for adopting four black babies, but this assessment didn’t sit well with me, as I was a firsthand witness to the cultural ignorance and racial bias they continually displayed. Often describing my younger siblings as “a little gang,” Larry and Ruthanne treated each of them differently based on the color of their skin.

Ezra, whose biological mother was white, had the lightest skin… Larry and Ruthanne often referred to him as the smart one, and it quickly became apparent that he was their favorite…

Zach, who had the darkest skin, was often treated the worst. Larry and Ruthanne made references to him being a “blue Black,” a variation on an old racial slur…

Unsurprisingly, Esther, the sole female adoptee, had it bad in the household.

In the racially determined hierarchy that existed in our household, Esther was just above Zach because her skin was a shade lighter than his. But growing up she had to endure the double burden of being both Black and female in a house that was white and patriarchal. Izaiah had nearly the same complexion she did, but the fact that he was a boy ensured that he received better treatment than her. Happy-go-lucky as a baby and a toddler, Izaiah grew more serious and cautious as he grew older, trying to avoid making the same sort of mistakes that had gotten Zach and Esther severely punished.

Larry and Ruthanne did all kinds of stupid and careless things with their adopted children. Notably, they exposed them to terrible racism and threats of violence when they lived in South Africa on a mission. They genuinely thought they could live amid Afrikaners in white gated communities and send their black children to white private schools with no repercussions. Most chilling to me was how these children were punished. They beat the children with long, thin glue sticks, the kind meant to be melted in glue guns for crafts.

This reminded me of Michael Pearl, the degenerate pervert behind No Greater Joy Ministries and his infamous How to Train Up a Child book. He advocates beating children with plumbing line and to do it until you feel like the child has been broken, like a horse. His method of discipline has resulted in the deaths of several children whose parents followed Pearl’s advice, and it’s no accident that most of those deaths were of black children adopted into white families. They died from rhabdomyolysis – in this case that’s kidney failure caused when constant beatings destroy muscle tissue to the point that it gets filtered into the kidneys and essentially clogs them. It’s a process not unlike tenderizing a steak with a mallet. You could easily end up with the same results with a glue stick.

Rachel’s family’s reaction to the four black babies was bizarre. One grandmother had no idea what to buy a black baby for Christmas. Rachel suggested that all babies like picture books and basic toys. The grandmother decided to get Ezra a drum he could play like a tribesman playing a bongo. There were few blacks in Troy, Montana, so whenever the children went out in public there was always someone who wanted to touch their hair and Rachel did her best to impart to these children that they were not exhibits in a zoo, curiosities to be touched on a whim. Her siblings suffered from repeated microaggressions, which are derided in some circles as being silly but can be a very real thing when you are one of a handful of black people in a white, religious area, adopted by people who may not have much interest in your overall well-being.

The elder Doležals seemed to overreact to the slightest misbehavior in their children.

On several occasions Larry and Ruthanne removed every item from their bedroom except mattresses and Bibles and changed the locks on the doors so they only locked (and unlocked) from the outside. For days – sometimes weeks – on end, they kept my siblings (with the notable exception of Ezra) confined to their prison-cell-like bedrooms, only letting them out to eat and use the bathroom.

As my younger siblings became teenagers, Larry and Ruthanne’s noble experiment of adopting four Black babies began to fall apart. Suddenly the cute Black children who could be kept in line with a glue stick had grown much taller than their tiny parents and outnumbered them two to one, and the do-as-you’re-told-no-questions-asked discipline tactics no longer worked.

The Doležals followed a script that other fundamentalist baby-collectors followed – bring a child from another culture into your home, take lots of photos with the cute children, force the kids to serve as a tangible demonstration of your Christian piety and charity, then get rid of them when they prove to be more than pets. No one knows how many Haitian children were brought into the United States for adoption into Christians families after the massive earthquake in 2010. Many children adopted from other countries by noble white religious folk have disappeared in the United States after their families tired of them. Bearing in mind that Rachel and Josh did not have it as bad as many fundamentalist children, the adopted children also fared better than many other black children adopted into white families. The Doležals were actually morally less bankrupt than many of their peers because their adoptions were legal, the children were issued social security numbers, and were legal citizens. It is also worth noting that when the Doležals sent their children away they still maintained legal parental status for all four children. They eventually signed Izaiah over to Rachel, and she became his legal guardian, but they never let their adopted children become wards of the state, something that happens with some adoptees whose families feel they are too incorrigible to raise.

That doesn’t mean they weren’t terrible parents to those children, though.

Once their adopted children started turning thirteen, Larry and Ruthanne started getting rid of them one by one. They turned Zach into the police for being aggressive and violent; as a result he either had to go on probation or reform school. They chose the latter, sending him to Lived Under Construction, a Christian residential treatment center in Missouri that reforms boys through manual labor. While they were there they heard about Shiloh Christian Children’s Ranch, a group home for abused and neglected children, and thought it would be a good fit for Esther after a girl at church had accused Esther of stealing her phone, which was later found under a couch. Zach and Esther spent their remaining middle school years in these institutions, and I was rarely able to communicate with them during this time.

Esther actually remained in institutional care until she graduated from high school. But when she was in the care of the Doležals basic elements of her care were not met. It’s a common problem with white people who adopt black children that they are unprepared for the differences between white and black skin and hair care regimens. Rachel taught herself about black self-care and made sure her siblings had appropriate soaps and lotions for their skin types but also made sure they had appropriate products and styles for their hair. Rachel Doležal knows a lot about black hair and how to maintain it and her own hair’s appearance in no small part enabled her to pass as black. But she learned such skills because her parents were unwilling to aid the four adopted children in maintaining good grooming or even skin health. In fact they may not have even known that black hair and skin needed different care than Ivory soap and a bottle of Suave.

Ruthanne especially loathed Esther’s hair.

One day, while taking out Esther’s braids prior to redoing them, Ruthanne got frustrated with the tangles. “Your hair is impossible,” she yelled. “I’m just done.” Using kitchen shears, she cut off Esther’s braids one by one. Stunned by Ruthanne’s insensitivity, Esther could only sit on the stool and cry as her hair fell to the floor. By cutting off Esther’s hair, Ruthanne was not only maiming Esther’s natural beauty but was also diminishing her self-worth.

I can’t imagine a mother doing this but I also believe this happened because the Doležals never really recognized the humanity of any of their children, least of all their black children. It is also very telling that she cut this child’s hair. Pentecostal women cannot cut their hair. Rachel and her mother had to maintain very long hair due to biblical verses about hair being a woman’s glory. This rule is so sacrosanct among some Pentecostals that the women achieve bangs by burning their wet hair with a curling iron – that way they can have some control over the style of their hair while following the letter of the law about female hair never being cut. Burning is not the same as cutting. But Ruthanne didn’t hesitate to cut Esther’s hair when she got annoyed with braiding it. She wasn’t just dehumanizing and defeminizing Esther, she was denying her spiritual sanctity as proscribed by Ruthanne’s very own religious beliefs.

Esther also claims she was molested by Josh Doležal, Rachel’s older biological brother.

When I told her what Josh had done to me, it freed her up to talk about her own experience. She was eerily matter-of-fact as she relayed her story. Esther never cries. While talking about being flogged with a baboon whip or forced to eat her own vomit, she’ll use the sweetest tone of voice you’ve ever heard. She employed the same incongruously saccharine tone as she told me how Josh had sexually assaulted her more than thirty times while he was living with Larry and Ruthanne in Colorado after getting his masters from University of Nebraska. She described two occasions when Josh forced her to perform oral sex on him and seven or eight instances when he performed oral sex on her. “Don’t tell anyone or I’ll hurt you,” she told me he’d once said to her. These assaults occurred when she was six and seven years old. Now that Josh had a two-year-old daughter, Esther was worried he might do the same thing to her.

I forgot to mention the vomit. Larry had a tendency to demand his children eat everything on their plate and if they couldn’t either due to being full or because they had an aversion to the food and vomited it back up they were expected to consume the vomit as well. Anyone who has studied these sorts of fundamentalist families has heard this story before. Not cleaning your plate when told to is considered rebellion against the father, who is God’s representative in the home.

Back to the sexual abuse. The case against Josh was strong enough to arrest him, extradite him to the state where the abuse occurred and to start criminal court proceedings but the mess with Rachel made it impossible to continue because the scandal brought into question a lot of honesty issues in Rachel’s testimony and her motives for encouraging her sister to bring charges. Her parents did their honor-best to ensure no one believed that Josh could have molested either sister.

…George Stephanopolous asked them about Esther’s case against Josh, Ruthanne responded, “Of all of Rachel’s false and malicious fabrications, this is definitely the worst. Rachel is desperately trying to destroy her biological family.” Stephanopolous called that “a very serious charge.” It was a very telling one as well. Think about it. What had I done to destroy that family? Josh was the one who had assaulted Esther, and Esther was the one who filed the charges against him. All I’d ever done was support her…

The family wagons circled around Josh and it seems like the situation with Rachel’s racial identity may have been his “get out of jail free card.” Charges were dropped but he was not cleared criminally of those charges.

One last thing I wanted to address: Some people have made a big meal out of the fact that Rachel referred to Izaiah as one of her sons. The assumption is that she tried to pass her brother off as her son to encourage people to think of her as black, and there may be some element of truth to that, which I will discuss in a later installment. But for now, the fact is that Rachel raised him when he was a baby and a toddler, more so than Ruthanne, and when Izaiah began to bristle at his negative treatment, he was sent to stay with Rachel for a summer. He eventually asked to stay with Rachel permanently, a request that the Doležals did not grant until they felt their backs against a potentially worse legal wall.

They’d initially fought the custody transfer, but when the court ordered an investigator to go to Missouri to interview Esther about the abuse she’d suffered, they backed down and agreed to grant me custody of Izaiah.

At the end they only raised one of their adopted children in their home continually from adoption to adulthood and it was Ezra, the lighter skinned boy who suffered from a failure to grow, likely caused from a terrible head injury he suffered as a baby (a genuine accident in the home, not due to abuse or active neglect).

Rachel’s parents were terrible parents and were even worse to their adopted children. Seeing how her younger siblings were treated was an important step in the journey Rachel traveled in adopting the guise of a black woman. Rachel is self-absorbed, arrogant, disingenuous, outright dishonest at times, and in some ways dangerous to black people but I also believe she cared deeply about her siblings and witnessing what they had to go through in white America informed some of her future decisions.

Her childhood and love for her siblings made me very sympathetic toward Rachel and I still feel that sympathy now. That doesn’t mean that the rest of this book isn’t one long look at a woman who has no idea how she comes across, how her attempts to spin her life positively actually reveal a nastier and less appealing side than she thought possible. Now that I’ve shown why I have some sympathy for Rachel, let me show you why I also hold her in a certain amount of contempt. Yes, America, you can do both. Come back Tuesday for Part 2. The next installments will be more entertaining – in depth looks at Rachel’s actual behavior, possible staged hate crimes, her practiced use of weasel words and outrageous justifications, and far less child abuse. They will also be shorter, a definite plus where this site is concerned.

Good stuff Anita. I find the mental gymnastics and fraud of this woman to be fascinating but I don’t really care enough to read her life story or even give her a penny for the book.

Thanks for writing this and doing such an in-depth look at this book and this woman. Rachel Dolezal is odious, but I do find the timing of her parents’ “outing” of her very suspicious in light of the details you bring up here.

I actually found your blog last week (trying to find any evidence for the claim that Joan Baez is a “self-described child ritual abuse survivor”) and I’ve been enjoying going back through your archives. Great blog you’ve got here!